The final story offers a window into the everyday reality of millions of black South Africans during the peak years of the National Party government’s crackdown on escalating resistance to apartheid.

In Guguletu, the same township where Amy Biehl was killed, another violent incident had taken place seven years earlier. Unlike the uncommon circumstances of Amy’s death, this incident was all too ordinary during apartheid’s most violent years.

In 1986, seven township youths were befriended and encouraged to raid the local police headquarters by an askari (a captured anti-apartheid activist who was coerced to work for the Security Police).

Before the raid could take place, the police ambushed and massacred the entire group of youths, while a school bus filled with children looked on. Such tactics were common at the time, especially when the police needed to show they were having success maintaining order.

Posthumously known as the “Guguletu 7,” their collective funeral became a galvanizing event, rallying thousands more to the cause of apartheid’s defeat. Through the TRC process, the long-withheld details of the murders have gradually been uncovered.

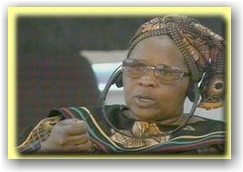

Our story focuses on the mothers of the seven murdered youths, who come to the TRC to publicly request reparations. The mothers testify about finding out about their sons’ deaths on the evening news, which announced that seven “terrorists” had been killed by the police.

After their own cathartic testimony, the mothers watch two policemen who have requested amnesty for the killings take the stand and admit their roles in the pre-meditated slaughter. One officer is black, the other white, one is remorseful and one not. (In an amnesty application the TRC requires only truthfulness, not remorse).

After their own cathartic testimony, the mothers watch two policemen who have requested amnesty for the killings take the stand and admit their roles in the pre-meditated slaughter. One officer is black, the other white, one is remorseful and one not. (In an amnesty application the TRC requires only truthfulness, not remorse).

At the conclusion of the hearings, the black officer, Thapelo Mbelo, meets directly with the mothers of the murdered youths to apologize for his actions.

After enduring more than ten years of police denials, the mothers assess to what extent their need for justice is satisfied by finally hearing the truth. One mother says, “As long as they are telling the whole truth, I’ve got no problem with the amnesty.” Others feel that simply admitting their guilt does not absolve their sons’ killers, and they express the desire for punitive measures.

As they speak out, telling their own truths and evaluating the killers’ testimonies, the mothers move through a process of transformation and empowerment. Having considered themselves to be victims, the mothers find a voice and an identity through their participation in the TRC, emerging with a newfound sense of themselves as full-fledged citizens in a progressive democracy.